Foreign milk producers are losing tremendous ground in China during the coronavirus pandemic, as nationalistic fervour influences sales amid souring relations with the United States and Australia.

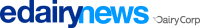

Overseas brands accounted for 23 per cent of sales on Tmall from January to August, according to the latest dairy tracker report published by China Skinny. Their share on the business-to-consumer online platform has steadily declined from 52 per cent in 2016 and 35 per cent in 2019, it added.

“We are surprised to find the stark decline since the outbreak, which bucks a trend of Chinese consumers’ rising milk consumption,” said Mark Tanner, managing director of China Skinny, a Shanghai-based market research firm. “Many foreign brands we talked to cited rising nationalism as the reason for the declining market share.”

Fresh milk imported from Australia, for example, slumped more than 20 per cent in July, according to Chinese Customs data, against the backdrop of trade and diplomatic spats as China curbed the import of Australian barley, beef and wine products.

Nationalism among consumers on both sides of arguments have risen with geopolitical tensions as Canberra called for an independent inquiry into the origins of the novel coronavirus and criticised a new security law imposed by Beijing on Hong Kong. China has accused Australia of working with the US to hinder its progress.

To illustrate the hostility within the industry, the Australian government last month blocked China Mengniu Dairy from buying some of Australia’s best-known milk brands under a A$600 million (US$437.4 million) deal it signed with Kirin Holdings of Japan first announced in November last year. It has also spilled into the media industry with questioning and detention of journalists.

“The soured relations will easily impact food business such as milk, wine and meat,” said Tommy Wu, a senior economist at Oxford Economics. “Unlike iron ore, which are widely needed for China’s infrastructure, a major driver for its economic recovery, milk is not strategically important.”

China’s import of dairy products increased about 15 per cent to US$10.65 billion in 2018, with milk powder making accounting for about 70 per cent of the amount, according to a Research & Markets report in January, citing customs statistics.

Chinese companies such as infant milk producer China Feihe, however, are not complaining.

“China’s dairy consumption has been fuelled by the people’s awareness to stay healthy after the pandemic outbreak,” a Feihe spokesperson said. “Chinese consumers have built up their confidence in home-made products as we have done a very good job at controlling the viral outbreak.”

Imported milk products were long favoured by mainland consumers after a melamine scandal in 2008 rocked the industry and eroded trust in local production, pushing them to the top of the shopping list on buying trips to Hong Kong.

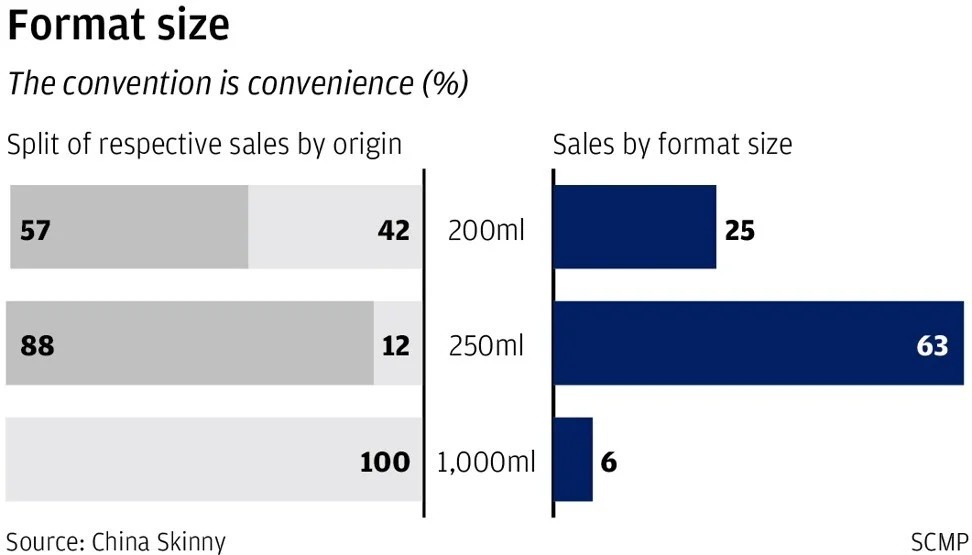

“The advantage has been largely narrowed as [foreign milk brands] cannot hit some basic needs, for example smaller and portable packaging” notwithstanding the nationalism factor, said Tanner of China Skinny. “Local domestic producers have also spared no effort in winning back their faith.”

Escalating geopolitical tensions may cost foreign milk producers the chance to gain a stronger foothold in China, which is expected to be the world’s largest milk market by sales in 2022, according to a Euromonitor forecast.

Geoff Babidge, chief executive of A2 Milk in New Zealand, said the situation is “regrettable.” He is not alone in the business community in saying that something needs to change, he said in an interview with the Australian Financial Review on September 18.

“We need to find some formula that works,” he was quoted as saying in the newspaper, noting that New Zealand appears to be able to maintain a healthy relationship with its key trade partners. “The political tensions appear to be escalating and we need a circuit breaker.”