The world looks dramatically different for South America’s dairy producers today than it did just one year ago. After seeing volumes contract in 2019 due to unfavorable weather and economics, milk production has returned to decisive growth in 2020. This achievement is being counteracted though by the tremendous uncertainty brought about by the coronavirus pandemic.

Most of South America’s major dairy producing countries have seen output move up significantly during the first half of the year. The gains were especially pronounced among the region’s key exporters. In Argentina and Uruguay, year-to-date growth clocked in at 8.7% and 3.9%, respectively, during the first six months of 2020. Important increases also have been witnessed by net importing countries along the continent’s Pacific coast, namely in Colombia and Chile.

Dramatically improved weather has supported production growth across most of the continent. Compared to the prior year, temperatures have remained mild and precipitation has been sufficient to sustain healthy pasture quality. Operating costs have also stayed moderate, which has helped to buoy farmer margins, even as milk prices remained static.

The glaring exception to production growth has been South America’s single largest milk-producing country, Brazil. Unlike much of the region, parts of Brazil suffered from drought during the first half of the year, which had negative implications for milk production. This situation was exacerbated by currency dynamics that rendered imported products uncompetitive and raised demand for domestically produced raw milk.

As in other parts of the world, consumer demand shifted radically as stay-at-home orders went into effect across South America in March. Food service effectively evaporated overnight, reducing demand for products like cheese and dulce de leche . . . Spanish for “candy made of milk.” On the flip side, retail demand for fresh dairy products rose. The emergence from these orders has been uneven, with some regions approaching “normal” while others remain under strict lockdown guidance.

Generally speaking, processors across South America have been successful in accommodating shifting consumer demand during the pandemic by rerouting milk into high-demand products. With select exceptions, there have not been widespread reports of either retail scarcity of products or of excess milk being dumped.

It is critical to acknowledge that this rebalancing was made easier by the fact that South America was passing through the low production season during the initial wave of the pandemic that occurred in the fall. As South America moves into the later months of 2020, milk production will rise seasonally in the spring months. While this will relieve pressure in tight markets like Brazil, other countries may shortly find themselves in a scenario of oversupply.

Export challenges

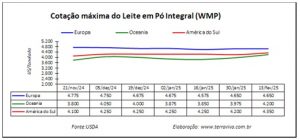

Especially among the region’s exporters, much of the excess milk supply is likely to be dried into milk powder, and especially whole milk powder. Under typical circumstances, a significant percentage of this powder would head to the export market. Of course, 2020 is anything but typical.

A dramatic currency devaluation of the Brazilian real, a key destination for Argentinian and Uruguayan product, has reduced the purchasing power of importers in that country. Though the real has recovered somewhat after hitting its low in mid-May, it remains over 20% cheaper than at the turn of the year. Furthermore, in the case of Argentina, currency controls implemented by the government to prop up confidence in the peso have left the currency artificially overvalued, reducing the incentives for exports.

Many of the region’s alternative export destinations are facing their own challenges with prospects dampened by the pandemic and economic fragility. Buyers such as Algeria and Russia have also felt the sting of weaker crude oil prices and are reining in spending as a result.

Without viable export destinations, much of the excess product could be forced into storage. While it is not uncommon to see stocks grow during the peak of the production season, if too much product accumulates, it will have the potential to overhang the market and put significant downward pressure on dairy commodity prices in the coming months.

If this comes to fruition, dairy producers in the region will face the real risk of seeing their milk checks shrink. Though farmer economics have been reasonably good the last few months, many producers are coming off a few tough years, and a prolonged period of low milk prices could be devastating.

Of course, there remain many unanswered questions, and the fluid nature of the pandemic promises to continue raising doubts. Even as the situation in South America has stayed relatively balanced thus far, there is reason to be concerned about the future.