Emerald Spring Dairy pushes back against misperceptions of industry’s environmental record.

“People hear cows pollute the earth,” said RitaYoung, shaking her head in frustration over what she calls a major misperception of how she and her family make their living. “We want to save the planet, too.”

Young, along with her husband, Maurie Young, and son, DarrinYoung, own and operate Emerald Spring Dairy east of Plainview and just across the line into Winona County.

In that space where agricultural business and environmental responsibility meet, perhaps no segment of farming suffers from the thepush-and-pull of those interests more than dairies. And, in Minnesota, perhaps none face the uphill battle of those in WinonaCounty.

The county has a cap of 1,500 animal units — 1,071 dairy cows– for each permitted feedlot. The Minnesota Pollution ControlAgency requires feedlots with 1,000 animal units or more to undergo an environmental review to obtain a National Pollution DischargeElimination Systems permit before obtaining a conditional use permit from their counties.

And while the rules for obtaining permits are fairly straight forward, the actual process can be anything but simple.

For the Youngs, environmental regulations represent a mix of both frustration and bemusement. And the response from the public about the 1,400 cattle they run — or about other large feedlots like their own — can be exasperating.

“My concern is they won’t rely on the science,” Rita said, talking about how regulators and lawmakers can impact a farm’s business. “I’m concerned they’ll let public opinion dictate them. We know the science proves our point.”

That science, she said, comes from many angles. For example, a 2009 study from Cornell University states that from 1944 to 2007, the U.S. dairy industry reduced its carbon footprint by 63 percent for the equivalent milk production.

“Farmers are problem-solvers by nature, so we’re always looking for better ways to do what we do, like raise crops or cattle,” Darrin said.

He noted another set of facts that show as the number of dairy cows in the U.S. over the last half dozen decades has dropped from 25 million to about 9 million, the industry has improved production by 17 percent. “You have 16 million fewer animals and produce more product,” Darrin said.

Despite the industry’s success reducing greenhouse gases — and the continued loss of dairy cows in Minnesota as small dairies shut their barn doors at greater and greater rates — Darrin and Maurienoted that if Emerald Spring is to expand under the current regulatory climate, it likely would not do so in Winona County due to the county’s animal unit cap.

“Currently, we own land in a different county,” Darrin said.

Maurie added, “That expansion won’t be here. We’re 600 feet from the Wabasha County line. It’s very frustrating.”

And there are other regulatory concerns.

“I think it’s inevitable the day is coming when we do have to measure it,” Maurice said, referring to greenhouse gas emissions from dairies.

Recently, the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency announced it would start creating an inventory of greenhouse gas emissions for every feedlot proposal that requires an environmental assessment worksheet.

The Youngs agreed that the dairy industry has been a leader in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. However, they look at California and the way that state has been focusing on such emissions for large feedlots, and they see a cautionary tale for Minnesota.

California has been requiring large feedlots to install methane digesters, facilities that collect manure and encourage the off-gassing of methane that is then collected for power generation. However, California has been paying farmers to install digesters, something the Youngs think is unlikely in Minnesota.

When it comes to environmental groups and farms, Darrin said, both sides share the same goals regarding sustainability and the environment. He said he welcomed the current regulations from the MPCA and pointed to some of the practices at Emerald Spring that show how the Youngs work to take care of the land.

The family plants about 1,900 acres of crops — most of which goes to feed their cattle — and includes about 500 acres of alfalfa in the rotation. They use cover crops, incorporate no-till into some of their crops, recycle both the wash water from the cows and the sand used for bedding, and, as part of a ConservationStewardship Program, will be planting a pollinator plot.

And, Rita said, her family’s story with the environment is a common tale among larger dairies across Minnesota.

“We’re able to produce a great quality product and still be great stewards,” she said.

Are dairies really a danger to climate change?

“The dairy industry has been very forward-thinking about ways to measure and ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions,” said MaurieYoung.

Owner and farmer at Emerald Spring Dairy in Winona County, Young is on the front lines of that reduction, planting cover crops, using manure as part of a soil-building process, and getting more milk per cow like the rest of America’s dairy farmers. According to toa study from Cornell University, the dairy industry has reduced the carbon footprint of a glass of milk by 63 percent between 1944 and2007.

That hasn’t stopped his industry – and large-animal agriculture in general – from getting on the wrong side of public opinion when it comes to climate change and greenhouse gas emissions.

You don’t have to look far to find tales describing the planet-wide dangers of animal agriculture.

Sunday night at the Academy Awards, Best Actor winner Joaquin Phoenix made a dig against the dairy industry during his acceptance speech. Last week, according to a story in the Edinburgh EveningNews, students at Edinburgh University narrowly voted against a ban of the sale of beef at campus cafés and restaurants.

Furthermore, following a court ruling the Minnesota PollutionControl Agency has decided to add an inventory of greenhouse gas emissions to all environmental assessment worksheets for new or expanding feedlots of 1,000 animal units or more.

In the middle of it, all are carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane. When it comes to animal agriculture, these molecules –particularly the two carbon molecules — are the new battleground in an environmental struggle between farming and climate sustainability.

“We’re so quiet about our success,” said Rita Young, Maurie’swife. Looking at the public and some state’s reaction to what she sees as misinformation about greenhouse gas emissions and dairy farming, Rita added, “You have to get common ground with them so they’ll be receptive to the truth on our practices.”

Minnesota’s Greenhouse Goals

Right now, said Peter Ciborowski, an environmental researcher with the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, is working to meet statewide greenhouse gas reduction goals. The first goal was a 15 percent reduction by 2015 from 2005’s emissions totals. The state missed that goal by a long way, only reducing emissions by 4 percent.

Those goals cut across seven different industry sectors including agriculture, electricity generation, transportation, residential, industrial, commercial, and waste. While the state overall has seen a reduction, three of the seven sectors have actually seen increases from 2005 to 2016, the latest year of data.

Most of the gain has come in electricity generation, but, Ciborowski said, that’s partly because it is the industry with the most regulation and – thanks to a legislative focus on renewable energy – has been the low-hanging fruit in the process thus far.

When it comes to agriculture, though, there is plenty of room for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions without taking extreme measures.

California Greenhouse Dreamin’

For Minnesota’s dairy industry, what’s happened in California is that extreme measure.

In 2015, the California state legislature passed a law allowing the California Air Resources Board (CARB) oversight of a goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent by 2030. A companion bill set parameters under which CARB could address dairy-related methane emissions.

To that end, the state has been funding the construction of methane digesters at dairies across the state. Digesters recreate the natural processes within a cow to convert manure into methane and solid waste to be used as fertilizer. The methane is then captured to use as fuel for power plants, which would then convert the methane into carbon dioxide.

So far, the Golden State has funded 64 dairy digester projects in its Dairy Digester Research and Development Program to the tune of just over $181.5 million. The state estimates these projects, once completed, will reduce greenhouse gas emissions by19.8 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent over a 10-year span.

However, Frank Mitloehner, a professor of animal science and air quality at the University of California-Davis, said California’sfocus on the beef and dairy industries misses the mark when it comes to the greenhouse gases that are adding to the environmental total.

“In my opinion, this is a smokescreen,” Mitloehner said. “Cattlesystems are not introducing new carbon to the atmosphere.”

Mitloehner explains it like this: The carbon involved in animal agriculture moves through something called the biogenic carbon cycle. Grass and other animal feed is made of carbon. The cows eat the grass, which is processed through the cow into methane, carbon dioxide, and manure. That manure is used as fertilizer, and the CO2and methane (which gets converted in the atmosphere into CO2 and water) eventually become part of the building blocks for the plants, and the cycle starts all over again.

By focusing on greenhouse gas emissions in feedlots, Mitloehnersaid, people concerned about climate change are missing the”800-pound gorilla that’s trying to sidetrack us.” That, he said, is the fossil fuel industry.

“Fossil fuels are responsible for 80 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions,” he said, pointing to the energy and transportation sectors as the big polluters. After all, he said, fossil fuels are essentially sequestered carbon we dig up and burn. “All of animal agriculture combined in the U.S. is 3.9 percent.”

Making Changes In Minnesota

Still, greenhouse gas emissions are becoming part of the feed lot approval process in Minnesota. After the Minnesota Court of Appeals ruled the MPCA had not completed its environmental review process on the proposed Daley Farms expansion, the agency has decided to add a greenhouse gas inventory to every future EAW required for large feedlot projects.

“We can argue all day whether we think this is necessary or not– and we think it’s not,” said Lucas Sjostrom, past-president of Minnesota Milk. “But if mitigating greenhouse gas emissions is the goal, this won’t help.”

Sjostrom said he realizes the MPCA had this action forced upon it by the Court of Appeals, but, like Rita Young, he wants to make sure lawmakers and regulators are making decisions based on facts.

“There are a lot of benefits to them when you put a dairy cow on land,” he said. That starts with soil building, capturing carbon in that loop Mitloehner described and creating healthy food choices for consumers. “Cows being added to any facility in Minnesota are not contributing to greenhouse gases.”

What he does not want to see, Sjostrom said, is Minnesota follow California’s lead in requiring methane digesters and putting capson greenhouse gases.

That, Ciborowski said, is unlikely.

“The state is first going to go the voluntary route,” Ciborowskisaid, relying on nearly 40 years in the industry as his guide.

He pointed to the energy industry example of Xcel Energydeciding to close its Sherburne County Generating Station and replace it with solar power. That was a matter of education and private industry making a choice, he said.

And, in Minnesota, good practices that farmers can voluntarily buy into still have plenty of room for reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. For example, no-till practices are used on only about 2percent of cropland, and cover crops are used on only about 5percent, he said.

“If we can get those up to 50 percent, that would be quite again,” Ciborowski said.

Battle over nitrates continues as new groundwater rules set to start

If you’re talking feedlots in Winona County, it won’t take long before the subject turns to one of the most divisive topics in karst country: nitrates in the groundwater.

At a meeting designed to discuss greenhouse gas emissions from large-scale animal feedlots, it didn’t take long for opponents of a proposed dairy expansion to start blaming animal agriculture –specifically, feedlots of 1,000 animal units or more — for the nitrogen in the groundwater.

“What efforts are you making to put a moratorium on new or existing factory farms?” asked Sonja Eayrs, whose family farm in Dodge County has well water far above the state’s health limit of10 milligrams of nitrate per liter of water, or 10 parts per million.

Winona County – as Daley Farms in Lewiston has sought to expand its operations – has become a battleground over large dairy feedlots and how those feedlots contribute to nitrate pollution of groundwater.

Health Risks, Old And New

That level has been set in Minnesota because of infant methemoglobinemia, or blue baby syndrome. The condition is caused by too much nitrates in water turning into nitrites, which block the ability of hemoglobin to carry oxygen in the blood.

But, according to a report from the Washington, D.C.-based environmental Working Group (EWG), the blue baby syndrome might be the tip of the iceberg when it comes to health concerns regarding nitrates in water.

“There are a lot of studies showing a link between nitrates and cancer,” said Anne Weir Schechinger, a senior economic analyst for EWG. Those studies, she added, show links to cancer — mostly cancers of the lower digestive tract — at 5 ppm andlower.

“What all those studies come back to is it’s a longer-term exposure situation,” Weir Schechinger said. “It’s exposure, time, and nitrate levels.”

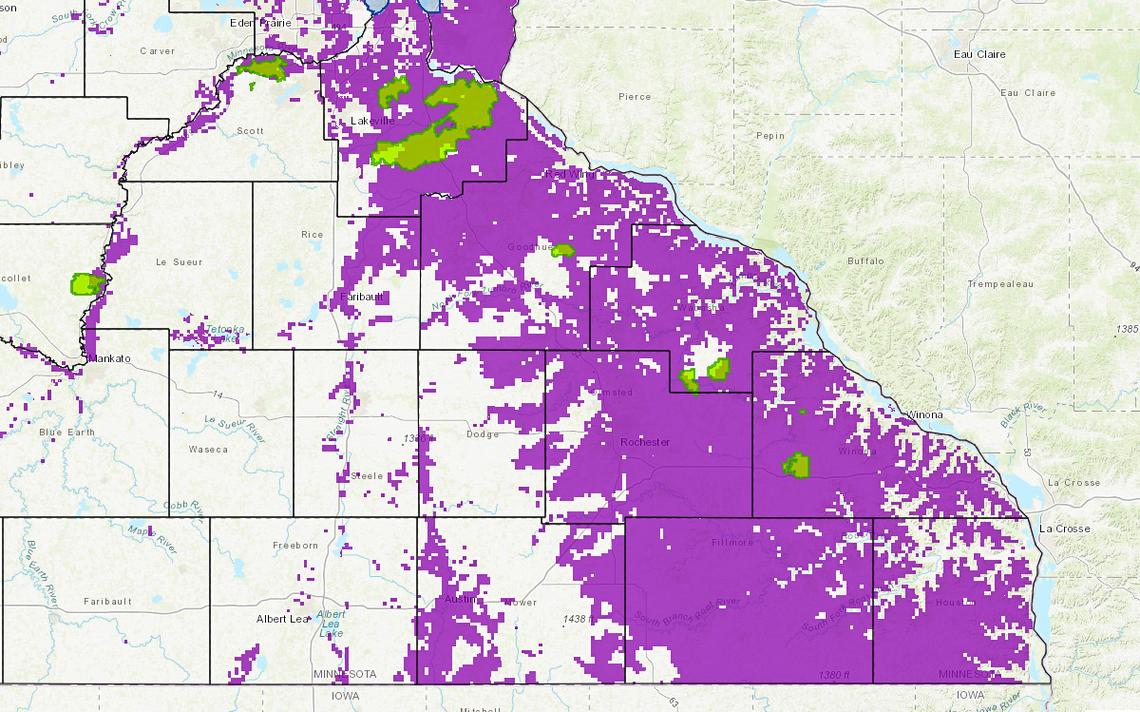

And Minnesota — especially southeastern Minnesota with its karst geology and reports of high levels of nitrate contamination across the region — is facing higher risks of cancer due to nitrates from agriculture. According to the Minnesota PollutionControl Agency, 72 percent of nitrates in groundwater originates from cropland. And nitrate levels in the Mississippi River have steadily increased since the 1970s.

“Many years of unaddressed nitrates from farm pollution have brought Minnesota to the brink of a public health crisis,” said Sarah Porter, a senior GIS analyst with EWG. “Now Minnesotans are paying for the state’s failure to hold farmers accountable for not keeping fertilizer and manure out of the water supply.”

The EWG report recommends setting a goal of reducing nitrate levels in drinking water below 3 ppm. To reach that goal, WeirSchechinger said, the solution isn’t to fix the contaminated water, it’s to reduce what gets applied on those fields in the first place.

Protection Rules Not Enough?

The state has already responded to the growing concern over nitrates in groundwater by enacting the Groundwater ProtectionRule, which has two parts for reducing nitrates.

The first is to ban fall application of nitrates in areas with vulnerable groundwater. That includes most of Southeast Minnesota’skarst region plus other row crop-heavy parts of the state. The ban for fall application begins in 2020.

The second part of the rule aims to protect areas around a public well, known as a drinking water supply management area, with high nitrates. For DWSMAs with nitrates above 8.0 ppm, the Minnesota Department of Agriculture will form a local advisory team to work with local farmers and agronomists to formulate a nitrate reduction plan.

Porter said the GPR won’t reduce nitrates in groundwater because it isn’t aggressive enough in battling the source of the problem, fertilizer application.

“Studies show 60 percent of farmers are applying nitrates above the (University of Minnesota) recommendations,” she said.

She also said that community wellhead protection plans, which have been enacted across the region in recent years, don’t have the required teeth to protect public water supplies. Furthermore, banning the fall application of nitrates should be done statewide, not just in sensitive areas.

Wells That Aren’t Well

Mark Thein, owner of Thein Well Rochester, said taking care to apply fertilizer is a must in the karst region.

“Whatever you apply on the surface that isn’t used up will migrate down at an average of 14 feet per year,” he said. “That’s rate in Southeast Minnesota.”

However, he was quick to add that placing the blame on large farm operations versus smaller farms is a false complaint.

“Whether it’s a large or a small farm, it’s the same fertilizer,” Thein said.

Thein, who drills, services, and caps wells in the region, said the EWG’s goal of reaching 3 ppm as a limit for nitrates is doable because most rural private wells are either already at that goal or so far above 10 ppm that a new well is needed. Not many wells fall into the 3 ppm to 10 ppm range, he said.

“The majority of wells in Olmsted County are at or less than 3ppm,” Thein said. “The rest are well above that level.”

Want to find an example of Minnesota farms out of compliance on the state’s buffer strip regulations? Don’t come to SoutheastMinnesota.

“We’re at 99 percent,” said Justin Hanson, the district manager for the Mower County Soil & Water Conservation District. “I talk to counterparts around the region. They’re all close to 100percent.”

“Ninety-nine point six-five,” said Daryl Buck, the district manager for Winona County’s SWCD. “We have a couple of landowners that have some parcels that aren’t compliant. Two are dry runs mapped as public waters. One of them I’m pretty confident will be taken off the list. Other three are not happy with the law.”

One of the state’s most contentious environmental regulations when it passed in 2016, the law required public waters to have a 50-foot buffer between crops and lakes, rivers, and streams. The buffer around ditches was set at 16.5 feet.

Farmers were required to be compliant along public waterways on Nov. 1, 2017, and private waterways a year later.

Buffers, according to the state Bureau of Water and SoilResources, are vegetative strips that help filter phosphorus, nitrogen, and sediment from cropland runoff before the water hits the streams, rivers, and lakes.

Buck said Winona County already had a 50-foot buffer ordinance for shoreland on the books, so getting the county’s landowners to meet the state law was not especially hard.

In fact, he said, getting farmers interested in environmental best practices is less a matter of resistance by farmers stuck in their ways and more a matter of getting the word out effectively.

“It’s kind of a revolution right now,” Buck said. “The cover crops and soil health stuff. The toughest thing right now is to show them that it works, how it works, and how it saves money.”

Anne Koliha, director of conservation planning for FillmoreCounty’s SWCD, also said farmers are embracing environmental practices. The county was already “easily at 85 percent” compliant when the buffer laws came into effect. “I’d say we’re probably 99percent now,” she said. “Farmers try to do their best on nitrogen application because everything costs money and with things being tight, it’s critical.”

Showing farmers how to change their practices to include cover crops, no-till, and soil-building applications – all best practices for nitrate reduction and carbon sequestration – is vital to getting buy-in from growers.

“We’ve been trying to get better with our method of communication with those folks,” Hanson said. “We need to get beyond talking about what’s bad and talk about solutions.”

Hanson said the state had offered grants for field day workshops, but some of that money has been drying up. Funding those grants again can be vital to changing farming habits.

In the meantime, Mower County SWCD reaches out to co-ops to try to reach more people and let them know how to make good environmental practices part of a good financial decision as well.

“Hard to be green when you’re in the red,” Hanson said.