At first glance, the numbers appear staggering. The American Farm Bureau Federation AFBF) estimates the Federal Order revenue sharing pools were short $527 in June, another $667 million in July and a further $286 million in August. That’s a combined shortfall approaching $1.5 billion.

In webinar after webinar, university, co-op and private dairy economists have tried to calmly explain the reasons behind these huge negative numbers. But even rational explanations of the Federal Milk Marketing Order (FMMO) system and its obtuse way of calculating minimum prices left most everyone shaking their heads and wondering if there is a better way. There might be—but everyone agrees there is no easy nor quick fix.

The economists assure farmers that the negative PPDs this past summer were not dollars totally lost from the system—or farmers’ pockets. In fact, some co-op economists insist there were no losses whatsoever to their members. University and private economists acknowledge there are some losses by some farmers, but the vast majority of farmers did not bear the full brunt of the negative PPDs.

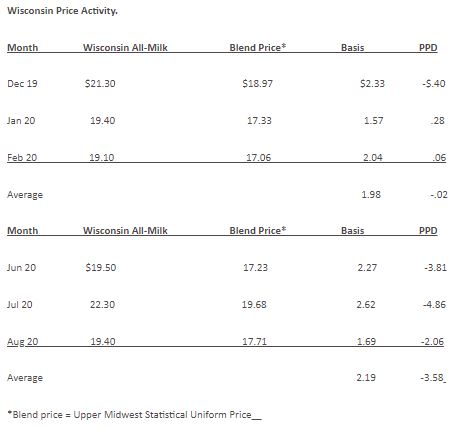

The Upper Midwest Federal Milk Marketing Order (FMMO) is a case in point. In late 2019 and early 2020, milk prices were rebounding and the PPD was in a more normal range. In the Upper Midwest, the December -$.40 PPD was actually a reflection of rising Class III prices and the lag effect of Federal Order pricing formulas. The average PPD for the three months of December, January and February was just a negative $.02. The basis—the difference between the all-milk price and the blend price–averaged a $1.98.

When the PPDs went hugely negative in June, July and August, the blend price was driven down. But Wisconsin milk prices were still strong, averaging $20. Even with these strong all-milk prices, farmers were expecting more—about $21 in June, $24 in July, $20 in August. The basis did improve from $1.98 early in the year to $2.19 over the summer. (See “Wisconsin Price Activity” table below.)

So while farmers did not receive the full benefit of rising prices through the blend price, processors did pay out a chunk of the negative PPDs through other premiums. “In June, it was considerably more than the $17.23 blend price,” explains Mark Stephenson, Director of the Center for Dairy Policy at the University of Wisconsin. “You’re going to see the negative numbers on your milk check, but you have to look at the bottom line.”

Mark Linzmeier, who heads up MARGINSMART Dairy Analyzer, routinely examines about 30 milk checks from Upper Midwest farms. These are large dairies, averaging about 2,000 cows each. So volume and quality premiums are likely in play. Most plants, he says, were not deducting the full negative PPDs in June or July. “A lot of the plants were $1.50 negative in June and $2.50 negative in July (about half of what the PPDs were),” he says. “Only one plant took the full deduction.”

Even then, not all of this is sinister, he says. Federal Order prices are calculated based on audited, whole sale cheese prices reported by cheesemakers. Linzmeier, who previously worked on the cheese processing side, says not every plant will or can sell cheese at these prices, and they may have other charges deducted. So they may not even have the revenue to cover the PPDs.

Some plants also might be making up for losses incurred in spring. “During the March and April 2020 lows, a cooperative may have cushioned the mailbox price above the weighted pool average,” says Megan Roberts, an Extension educator in agricultural business management at the University of Minnesota. “Now that market prices have risen, they may need to even out payments.

“Or, if a cooperative had to resell milk below market price during stay-at-home orders, it may have spread the loss across members by using deductions, lowering mailbox price. If a cooperative uses bases/excess pricing plans, pricing for excess production has been particularly hard hit,” she says.

So why do PPDs go negative? Here’s Stephenson’s explanation:

“In 7 of the 11 Federal Orders, farms are paid on the basis of the Class III component values for protein, butterfat, and other solids (mostly lactose). When Class prices behave according to the usual expectations –Class I price is the highest value – there is money left over in the pool after withdrawing the Class III component values and that remainder is distributed to producers based on the volume of milk sold. Expressed in dollars per cwt., that remaining value is called the Producer Price Differential, or PPD.

“The PPD can be thought of as an accounting exercise, but there is a purpose to this approach as well. For the seven orders in which this system is used, there is a notable volume of cheese production, and it was believed to be a good idea to reward farmers for producing higher protein milk, which is not one-for-one the same as higher skim solids milk. Once it was decided to pay out to producers on the basis of the same components that are used in Class III, and only in Class III, then it made mathematical sense to begin the blend price calculation with the Class III price and add (or subtract) whatever moneys remained in the pool.”

Negative PPDs are mostly a function of timing, says Stephenson. “We did not anticipate the possibility of a Class III price, calculated after the advance Class I price was already announced, rising so much in the span of a few weeks so as to result in a Class III price that was higher than the total average amount of money paid into the pool. Thus, we can have a month where the Class III price is higher than the blend price, and in this instance, the PPD calculation will be negative. All that means is that we paid out more money to producers in Class III component values than we collected from plants across all classes of milk. For farmers, it is really just a curiosity in the accounting method.”

Except for cheesemakers, who must pay into the pool when Class III is higher than the blend price. Cheesemakers have an out, however, in that they can depool and avoid these payments. Without depooling, the negative PPDs experienced this summer would have been much less severe.

There’s a second problem, unintentionally created in the 2018 Farm Bill when the formula for setting the Class I price was changed from using the “higher of” Class III or Class IV and simply adding the historical Class III/IV average of 74₵/cwt. The change was made to make the Class I price more predictable, allowing farmers who sell primarily into fluid markets and fluid handlers to better use risk management tools. But the rapid rise in Class III prices this spring far out-stripped that 74₵ average, thus exasperating the negative PPDs.

There are a number of fixes being suggested. “The large amount of temporary de-pooling that occurred has raised concerns in some markets and could be addressed by stronger pooling requirements,” says Jim Mulhern, president and CEO of the National Milk Producers Federation. “But those issues should be addressed on an order-by-order basis.”

Others have suggested only pooling Class I differentials. Still others advocate eliminating advanced pricing and going back to using the “higher of” Class III and IV. “Nothing short of this (latter option) would guarantee an elimination of negative PPDs and thus the incentive to depool,” says John Newton, AFBF chief economist.

Mulhern also offers this warning: “Making long-term policy changes because of short-term, Black Swan events and unprecedented conditions rarely results in good policy. Instead, it can create a worse situation over the longer term that permanently reduces farmer income without remedying any fundamental market factors or conditions.”

In the end, farmers need to keep in mind that the spring and summer of 2020 presented extraordinary market conditions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. First, there was the huge price declines due to the closure of schools and restaurants in spring. And then there was the skyrocketing of prices, led by cheese markets, brought on by the Trump Administration’s announcement of $1 billion in dairy food purchases schools, food banks and its Food Box program on short delivery dates.

These purchases, and their short time frame, sent cheese prices sky rocketing. “I don’t think there is a good short-term solution to [Federal Order issues] when prices go up so surprisingly,” says Marin Bozic, a dairy economist with the University of Minnesota.

“It’s important to keep in mind that while it was the federal government’s purchases of dairy products for donation that largely caused the ‘problem,’ that outcome was vastly superior to the alternative of no government action,” Mulhern says. “Yes, there would likely have been no negative PPDs. But farm milk prices would have been much, much lower than they have been as a result of the government’s actions.”

“The first thing we have to do is decide what the problem is,” Bozic says. The worst thing the industry could do is to rush into a solution without thorough analysis and debate. A national, Federal Order hearing is much more conducive to learning all sides of the debate than a quick, legislative fix largely done by lobbyists, he says.

Stephenson agrees, and brings up this point: “Federal Milk Marketing Orders are a fluid milk institution living in a manufacturing world.”

In the 1940s, 65% of milk in Federal Orders was fluid. Today, that number is less than half that. Price levels have also changed.

“A $3 Class I differential on top of a $5 manufacturing price when Class I utilization was greater than 60% equaled 26% of your milk check,” Stephenson says. “But a $3 differential on top of a $16 manufacturing price when Class I utilization is less than 30% is 5% of your milk check.

In regions like the Upper Midwest or California, it is much less—about 1%. “Federal Orders aren’t returning a lot to dairy producers [in high manufacturing areas],” he says. They do provide services and order that are important. But you almost have the wrong tool for the job.”